Richard (The Beak) Stratton, former Vietnam War POW and USN Captain (ret.), wrote “The Tales of South East Asia” in answer to questions from both his children and grandchildren over the years. These stories touch upon many of his experiences while held captive by the North Vietnamese in their prison system for over six years – some memories are humorous, all reflect a need to maintain communications, faith, hope, perseverance and honor to survive. The Beak no longer writes, but has granted me permission to share that part of his life on this blog. I’ve chosen four tales to share – posting a new one every other day for the next week. Be sure to subscribe to my blog at the end of this article and be notified by email every time something new is published. The final installment will include website links to both The Beaks‘ website and the Vietnam POW website.

Tales Of South East Asia

The occasional memoirs of “The Beak,”

a.k.a. Capt. Richard A. Stratton, USN [ret.]

![]()

Celebrating 15,011 days of Freedom since

March 4, 1973

Name: Richard Allen "Dick" Stratton Rank/Branch: O4/US Navy Unit: Attack Squardon 192, USS Ticonderoga (CAW 19 CVA-14) Date of Birth: 14 October 1931 (Quincy MA) Home City of Record: Quincy MA (family in Palo Alto CA) Date of Loss: 05 January 1967 Country of Loss: North Vietnam Loss Coordinates: 193400N 1054700E (WG824634) Status (in 1973): Released POW Category: Aircraft/Vehicle/Ground: A4E

LtCdr. Richard A. Stratton was an A4E pilot and the maintenance officer of Attack Squadron 192 onboard the aircraft carrier USS TICONDEROGA (CVA-14). On January 4, 1967, he launched in his A4E “Skyhawk” attack aircraft at 0703 hours for his 27th mission on an armed reconnaissance mission over Thanh Hoa Province, North Vietnam to destroy the My Trach ferry. The ferry was not found; however, four large barges were located one mile up the river. LtCdr. Stratton rolled in on the barges and launched his rockets. Almost immediately, he began to experience a rough running engine and fire. It was suspected that foreign objects/debris (FOD) was ingested into the engine on firing his rockets. He immediately turned his aircraft for departure out to sea. His wingman did not see an ejection, but did spot a fully deployed parachute landing in a tree near a small village. An emergency beeper was heard for 1-2 minutes, and it was suspected that Stratton was captured immediately.

Radio Hanoi broadcasts of the capture of a pilot confirmed Stratton’s Prisoner of War status. He was held in the Hanoi prison system and used in numerous media events in attempts to bolster the propaganda effort. One such event was a heavily commercialized “confession” and bowing to the Vietnamese in a March 4, 1967 photo.

The American POWs agreed that they would not accept early release without all the prisoners being released, but in early August 1969, the POWs decided it was time the story of their torture was known. Allowing someone in their midst to accept an early release would also provide the U.S. with a more complete list of Americans being held captive. A young seaman, Doug Hegdahl, together with Bob Frishman and Wesley Rumble were released from Hanoi as a propaganda move for the Vietnamese, but with the blessings of the POWs. When they were about to be released, Stratton told Hegdahl, “Go ahead, blow the whistle. If it means more torture for me, at least I’ll know why, and will feel it’s worth the sacrifice.” Eventually, after world pressure ensued, torture of American POWs ceased.

On March 4, 1973, Stratton was released in Operation Homecoming with a total of 591 American POWs. He had been held 2, 251 days. He was awarded the Silver Star, the Legion of Merit with V, the Bronze Star with V, Air Medal, the Navy Commendation medal with V, the Combat Action Ribbon, and a Purple Heart, as well as the POW medal.

He continued his Naval career and retired with the rank of Captain in 1986 after 31 years of service. He is a clinical social worker, is nationally certified in drug addiction counseling, and enjoys working with a family service center as well as private practice.

He and his wife, Alice, reside in Florida. Alice Stratton holds the position of First Deputy Assistant Secretary of the Navy for Force Support and Families. Dick Stratton is still concerned about the men who were left behind in Vietnam. He has been active in leadership in the National League of Families of POW/MIAs, and has served on its board of directors.

The Stratton family maintains its military ties — son Patrick and wife Dawn Stratton served with the USMC in the Gulf War and in Saudi Arabia. Another son, Michael Stratton also served with the Marines in the Gulf War and in Saudi Arabia. Son Charles and wife Joanna reside in Michigan. Grandbaby number 1, Amanda Jean, was born 12/02/96.

Reflecting now on his captivity and Homecoming, Richard Stratton says his time in captivity was “shore duty” and “God Bless Richard M. Nixon and his courage to bomb Hanoi — God Bless CAG Stockdale and BGEN Risner for their courageous leadership — God Bless our wives’ loyalty and public fight for our release.”

.

THE MAD BOMBER OF HANOI

.

This is a tale based on shipboard perceptions during a wartime deployment to Southeast Asia. The account claims no historical accuracy but reflects the mood and understanding of’ a ready room on a 27-Charlie carrier in late 1966 and early 1967. Perceptions become reality to those who hold them. Remember that the raconteur is an ex-convict who distinguished himself by shooting himself down in combat. Caveat emptor (“let the buyer beware”).

In the late fall of 1966, when the USS Ticonderoga (not the one sailing around now,. but the one you are shaving with–CVA-14) hit Yankee Station, the philosophy of escalated response dominated all military strategy and tactics. Robert S. MacNamara and Lyndon B. Johnson were running the war from the basement of the White House. Rules of engagement were more protective of the enemy than of the American fighting man. Significant strategic areas such as major ports, the Chinese border, and the district of Hanoi were protected American-imposed restricted areas. These areas could only be targeted with permission from the White House.

The micro-managed, cost-effective. zero-defect war effort had resulted in a shortage of all kinds of equipment from flight suits to rockets and borings. Success was measured by sorties flown and tonnage dropped, the air war equivalent of body count on the ground in the South-measures of questionable utility and morality. Most of our time on station was spent chasing water buffaloes and bicycles up and down trails and planning for the three strategic targets allotted per month by the White House.

Rumors of an early end to the war abounded. The British Prime Minister was scheduled to make a swing through Southeast Asia, exploring the possibilities of peace. The word was going around that secret talks were about to be held between the United States and North Vietnam in our embassy in Warsaw. The bottom line was that the entire world diplomatic community was hyperactive in exploring peace initiatives. Meanwhile, a realistic assessment by military people on the ground in Vietnam gave a prediction of a twenty-year involvement at the current rate of commitment to attain an objective enabling the Republic of Vietnam to stand alone against the Northern invader. All of this made little difference to deployed air wings who had learned to live from line period to line period, sortie to sortie, day to day. We were spending about forty days on the line, t1vin- about 2.5 sorties per pilot, per day, and alternating between day and night sorties with our sister carrier. The thrills were the occasional Alpha Strikes against targets of strategic importance. Two years into the war, Mr. McNamara finally figured out that the uniservice, unisex pumpkin-orange flight suit was not contributing to the longevity of airmen on the ground, evading in the jungle. He finally authorized new flight gear, which, of course, was not in the supply system by the time the Tico deployed. Pilots were permitted to buy their own gear [at their own expense]; and I selected Marine fatigues as being my best shot at survival – I was to pay a price for this.

We were short of Zuni five-inch rockets and made up for the lack with Aero 7D rocket packs, many of which lacked effective speed brake, an advantage-e that a fully loaded A-4E does not really require. Additionally, the 2.75-inch FFAR was not noted in the fleet for its accuracy or reliability–I was to pay a price for this as well. In December of 1966, we were assigned a target within the Hanoi restricted area, the Van Dien Truck Repair Facility, which was in the district of Hanoi but not the city of Hanoi.

The Alpha Strike went off tolerably well. I missed the show because of a nose gear malfunction and had to go back to the ship. Diplomatically, the strike was a bomb. Ho Chi Minh, the President of NVN, accused us of bombing the sacred city of Hanoi and hitting civilian targets. Harrison H. Salisbury of the New York Times rushed to Hanoi at the invitation of NVN and dutifully reported damage to non-military targets (shades of Peter Arnett in Baghdad). LBJ countered by denying the accusation and stating that those defective Russian SAMs had obviously fallen back upon the city. Uncle Ho called LBJ a liar, not a very original accusation, and called off any and all peace initiatives, vowing to defend the motherland for ten, twenty, or forty years against the American imperialist aggressors. McNamara’s response was to call another of the ubiquitous “bombing halts” for Ho to contemplate his navel or his sins. I never figured out which, and neither did Ho.

Tico finished up its line period and returned to Subic Bay for a stand-down. The Communists, of course, used the couple of weeks to resupply and rebuild their bridges. Our leaders flew up to Atsugi Base, conveniently near Tokyo, for a “planning conference,” while we conducted FCLPs at Cubi Point for the replacement pilots. After the planning conference, XO couldn’t get his bird started. So with true entrepreneurial spirit, he scouted the flight line and stole the best-looking A4E from the Nippi Rework Facility flight line, a Marine Corps plane sans log books, and returned to the ship, now steaming back to Yankee Station. Our maintenance crew painted up the stolen steed just like a circus wagon with all the air wing colors, christened it “Double Nuts”(Modex 400) for the use of our CAG, and sent it into combat.

About the second day out, I got a call from my best friend Mike Estocin (later awarded the Medal of Honor posthumously) asking me to take his first hop of the morning since he had an Ops Officer meeting to attend with CAG. Not yet awake, I violated a cardinal rule of survival–don’t volunteer for nothin’-and took his hop. It should have been a piece of cake as it was the weather hop. The only “weather” in the “weather hop” was that it didn’t make any difference whether the weather was good or bad; we were going to fly anyway. The supposed minimums were five-thousand-and-five; the weather was below minimums that day, and they flew all day. The benefit to you, as the recruiters say, was that after checking the weather out at dawn, you could recce the coastline for any cargo carrying junks that had not made it into a river mouth for daylight hours. McNamara had a rule of engagement that said you could only attack a junk traveling from North to South and then only after you had flown by to verify with your own eyeballs that it had deck cargo, obviously enhancing your element of surprise.

Well, my wingman and I found some targets. I made a run on a junk, using my five-inch Zunis, and then a short distance away I found a bridge section tied up along the shoreline and unloaded my Aero 7D packs on that hummer. (No, it was not a second run on the same target; my learning curve is not that flat.) True to form, the rockets fired; the stabilizing fins did not extend, causing instability in the rockets; and the rockets collided.

The warheads did work (good); however, the debris from the explosions went into the intakes (bad). The J-52 engine does quite well on air but has a problem with scrap metal. I developed an instantaneous love affair with the surface navy and turned seaward. The engine gave up the ghost, taking off the tail in the process. The A-4E is a wonderful, tail, it has all the aerodynamic characteristics of a free falling safe.

I was at a decision point. I had just broadcast my farewell address to the entire Seventh Fleet – “Oh S__t!” and was debating my next move. Why the debate? The A-4’s ejection seat is powered by a rocket in front of a fuselage tank with 1,200 pounds of JP-5 in it, and I had just had an unfortunate experience with a rocket from the lowest bidder. I was moved to action by the echo of my wife’s last words to me: “Don’t you dare die and leave me with these three little bastards!” That’s a commitment. I ejected. Did you ever have a bad day? I landed in the only tree behind the only house in five square miles and was a prisoner before I had my helmet off.

I was stripped to my skivvies and shown off at every crossroads, village, and hamlet within a four-hour walking distance. I was blindfolded, “executed” with a single rifle shot, and rolled into my grave for the afternoon. At dusk, I was on the road again by foot until about midnight and then transported on the back of a 2×8 to Hanoi, arriving at the Hoa Lo Prison (Hanoi Hilton) at daybreak. I foresaw no big problem, having been through SERE training twice in the Cleveland National Forest (sic!), assured that there was no such thing as torture, and convinced that I just had to tough it out for 48 hours to earn my way into the “bad guy’s” camp. I would spend the rest of the war playing Hogan’s Heroes until my great escape. Ha!!

Interrogation started off as a piece of cake. I was frightened, but playing the game of name, rank, serial number, and date of birth. As I was to find out later, the interrogation followed a set pattern of five stages: the history lesson of the enemy’s cause in converting you (boring); the exploitation of your perceived weaknesses (race, religion, rank, homesickness, family, etc); the appeal to your military discipline (you obey orders in your army, and you are now in our army; therefore, you will obey our orders); the application of physical force (no big deal for street fighters or contact sports survivors); and the application of torture (controlled infliction of pain with the objective of gaining compliance with something you find to be morally reprehensible).

Picture yourself being tortured to admit, as a squid, that you are a Marine. Remember the Marine fatigues and the stolen A-4? (The parachute seat pan had a sergeant’s signature on the packing slip.) I have nothing against the Corps. I admired my Preflight DIs (Sergeants Jones, Livermore, and Raphael – start NavCad Class 19-55; finish NavCad Class 32-55, learning curve on the obstacle course relatively flat). Two of my three sons and my daughter-in-law are Marines. But that was a bit much. What were they after? A little bit of military information. What was the next target? I didn’t know; that’s why Mike had to go to CAG’s meeting. What new weapons did the Taco have? The Aero 7D Rocket pack with 19 independently targeted warheads, the destination of which even I did not know. From what altitude did I drop my bombs? Beats the hell out of me. That’s why I spent all that time on targets at NAS Fallon, developing my seaman’s eye. Pick a number, any number, but whatever it is, stick to it.

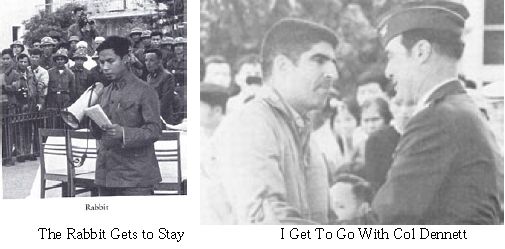

It took me six months to figure out what it was they were after-propaganda. As the first bomber pilot to be shot down after the Christmas bombing halt and raid on the sacred city of Hanoi, I had been designated to be the “Mad Bomber of Hanoi.” Of the guys captured in North Vietnam from 1965 – 1968, 95% were tortured; 95% were not given the option of death; and 95% gave more than name, serial number, and date of birth – not bragging, not complaining, just a factoid that underlines the skill of the torturers. As they had me talking, hopefully a bunch of nonsense, they had a political cadre reviewing my production, adopting my “style” and, unbeknownst to me, writing my “confession.” We named this guy the “Rabbit,” in recognition of his distinctive ears and overbite. After two weeks of torture, beatings, and isolation, I was transferred to another prison–“the Zoo”– where I thought the worst was over.

About a month later, during one of the routine interrogations, the Rabbit showed me a confession and asked for my opinion; it was difficult to keep from laughing. It had an A-4 leading a strike on downtown Hanoi, targeting pregnant women, children, dikes, dams, and pagodas. A single A-4 was loaded out with every weapon on the pilot’s weapons weight card, which they had retrieved: napalm, mines, rockets, CBUs, and HE down to the Mk 76 practice bomb. It related incipient mutinies on board ship, anti-war pilots defecting, and pilots loading up on whiskey for liquid courage. My laughter stopped when he informed me that it was my confession to be given in the Hanoi soccer stadium. His response to the observation that such an attack never took

place and that I had never even pulled liberty in the town made a certain measure of sense. “No matter; somebody did it. It might as well be you.” Then followed the usual forms of coercion for naturally I would not cooperate with their farce. They realized that if they let me recite anything they could not control it. The settled on a tape recording to be played from behind a curtain like some form of a Vietnamese karaoke performance. I was pushed out before a grouping of the Hanoi diplomatic and Press Corps to make a polite bow. I played the Manchurian Candidate;

they got the hook and hauled me back to jail none the wiser as to how they had been snookered. In fact it was six months before I received confirmation from the new shootdowns that the pantomime had worked. However, I was to have the last laugh. I was eventually going to the land of the big PX, and the Rabbit had to stay.

What are the lessons I learned? Don’t volunteer for nothin’. Long deployments enhance marriages (thirty-two years) since they cut down the amount of time your wife has to smell your cigars. Never land in the same place you just got through bombing and strafing. If you cannot take a joke, you should not be wearing a set of wings. Jettison Aero 7D rocket pods without nose cones as soon as you get out of sight of the ship. Americans seeking publicity who appear in enemy capitals during a shooting war are giving aid and comfort to the enemy (treason), no matter what the press tells us.

Unattended Navy brats tend to go Marine Corps. The A-4 ejection system works at 2,000 feet, 220 knots, nose down, without a tail, and in a spin. Practice your final words, so that you do not embarrass yourself and your family in front of your shipmates when you buy the farm; you can do better than “Oh S__t!” You can tell folks you learned this from The Mad Bomber of Hanoi.

A-4s forever!

Richard A. Stratton

July 4, 1991

Atlantic Beach, Florida

Foundation, Fall 1991

Naval Aviation Museum Foundation

Click below for more articles from this series:

The Incredibly Stupid one at the Hanoi Hilton

Who Won the Army-Navy Game (2 of 4)

Juicy Fruit Secrets (3 of 4)

Release – The March Hare and Scrambled eggs (4 of 4)

Thank you for taking the time to read this. Should you have a question or comment about this article, then scroll down to the comment section below to leave your response.

If you want to learn more about the Vietnam War and its Warriors, then subscribe to this blog and get notified by email or your feed reader every time a new story, picture, video or changes occur on this website – the button is located at the top right of this page.

I’ve also created a poll to help identify my website audience – before leaving, can you please click HERE and choose the one item best describing you. Thank you in advance!

We can never forget these stories or people.

LikeLike